Twists of Fate, by Paco Roca

2013, English edition 2018

This was a lucky buy over the summer. I'd never heard of Roca, and it was 75% off. It ended up being one of my favorite things I read last year, just as a good, solid comic. Last week I reread it as part of a comic "book club" and I appreciated it even more.

|

| The cover is a repurposed panel from the book |

I think this is a "great" comic. When I say that, I'm not saying it's life-changing, or game-changing or any of the other adjectives that are usually applied to "great" comics. This is a solid 300-page story that is personal, interesting, and well-told. The art is impeccable and is in service to the story, not generally flashy or suited to pin ups. This is a top quality book lacking things that usually bring hype to a book. But this kind of book is in very short supply in the English market, when it should be the norm. When I first finished reading this last summer, I was immediately depressed how many times I had seen something about DC's Three Jokers without any interest or desire to, but had never once seen any digital ink spilt on this book. It became an underdog in my eyes.

|

| The original Spanish cover is a graphically more interesting, but conceptually harder to understand at a glance |

Importantly, the book is a translation from Spanish, and it was already five years old when it was released by Fantagraphics, so it probably was less of a priority for the company than their American artists who can attend domestic release parties and participate in English language social media, That's conjecture on my part, I don't know. But I understand there are many reasons that Roca's work doesn't receive coverage anywhere near DC's flagship characters. It's just a depressing reality of America's comic industry. |

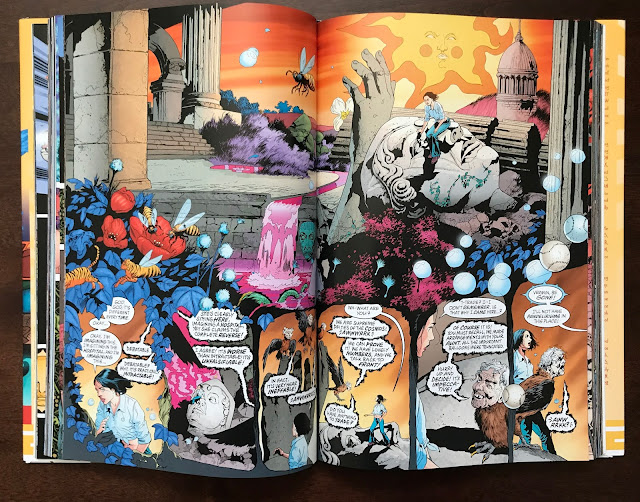

| Roca uses a different graphic style on the present and past storylines. The color makes the war story more vivid, though as a secondhand retelling, must have had some artistic license taken |

So what is it about? The book is written, drawn and colored by Roca, who interviews Miguel, a 90-something Spaniard living in France, about his experience helping liberate Paris in WWII. Roca makes the interview part of the book itself, and so we see how Miguel is processing these memories from some 65 years before. The WWII narrative is the bulk of the book, but the contrast between the two periods, and how Miguel has compartmentalized this time of his life is a major part of it. The closest thing to a friend Miguel has, a divorcee neighbor who's known him since he was a child, knows nothing of Miguel's history despite living close to him for decades. Without Roca's interest in interviewing him, Miguel might never have discussed these events again. |

| Miguel "only killed fascists and only in combat." |

One of the key themes of the book and Miguel's memory of that time is that Miguel killed lots of people. It was war, that's what you did. Miguel had fled the fascist Franco regime in his home country, and spent some years in refugee/concentration camps in North Africa. He and his mates had a deep hatred of what the fascists were doing to his country, and by association, what the Nazis were doing in Europe. As Miguel drudges up these old memories, he is pained. He has had decades to live with the deaths he saw and was part of. He is never proud of killing, but he never shows regret either. From Roca's portrayal, it feels like it's taken a toll on Miguel, and is a reason he hadn't spoken about it since the war. |

| In one of the most affecting scenes, Miguel and a small group of soldiers find Germans at a small French farmhouse and kill them. They then sit down at the table to eat the food the Germans were about to eat. The one soldier was shot in the head, having just taken off his helmet to eat. Miguel sees the photo of the dead soldier's girlfriend tucked into the helmet. |

The book focuses on the participation of Spanish in the war, as opposed to Spain which sat the war out. Throughout the book though, there are stories of dispossessed people from around Europe; Poles, Italians, French, even Germans against Hitler. Nationality is important to these people, and it's a snapshot of a world very different than mine. My upbringing in Canada lacked the passionate connection to my roots that the people in Miguel's world have.

|

| "A Frenchman..." "Armenian." |

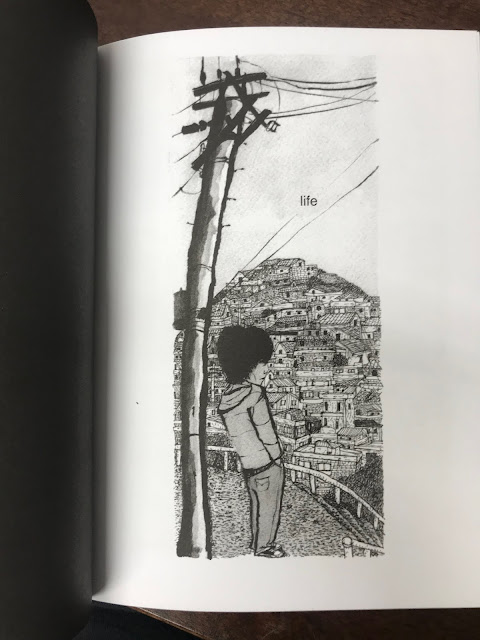

The art in this is gorgeous, even though the subject matter is quite dark. I think the closest comparison to Roca's art in the American market would be 1990s David Mazzuchelli, the work around Batman: Year One and Rubber Blanket. Roca's work has a strong foundation to its structure: the buildings, the vehicles, the land, and the people all look like they should, but are rendered in a loose line that lets it all breathe.  |

| He draws so many tanks, jeeps, airplanes and other vehicles that it makes my head spin. Many artists make it a point to avoid drawing cars |

Indeed, though the characters in the book can be difficult to distinguish in places since they all have the same clothes and similar military haircuts, they each have their own facial features. And Roca animates his characters, panel to panel, so that they move like people. Not a single corner was cut (I'm looking at you, Alex Maleev, who has a pocket stuffed with corners he's cut). |

| This is deceptively difficult cartooning |

As a very amateurish cartoonist myself, this is the kind of book I might pull out on a Sunday to take lessons from.I liked this even more on the second read. The second time with it, I knew the broad strokes of the plot, and focused more on Miguel as a character. Roca is juggling a lot with this book, and like a lot of books with a dense plot, it often takes most of your concentration at first exposure just to know what's going on. Once you have a handle on that, you can focus on appreciating the details.

I felt much more for Miguel this read, and while you get a picture of who he is, you don't get to go in his head. Roca keeps a distance and relates what Miguel says. He doesn't try to explain what Miguel thinks.

I don't know how much Roca is writing this to interact with the politics of the world today, but it gave me a lot of reflection about the life I'm leading, the number of democratic places in the world starting to trend toward fascism, and how for the generation that won WWII, fascism was obviously the enemy. Growing up in the late 20th century in Canada, I have to wonder how much I take peace and safety for granted, and how real the danger to it is.

This is a rich work, and it seems to have already fallen through the cracks of the English language audience. Roca's still working and making great books (Winter of the Cartoonist just came out in English last year), so maybe in time he'll be able to capture some of the success in America that he's had in Spain.