The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, by Adrian Tomine

2020

What an enormously frustrating book.

|

| AAA production values |

I love Tomine's work. I really do. I was buying Optic Nerve in the 90's, I love his New Yorker illustrations, and Killing and Dying is one of my favorite comic collections period. Killing and Dying is incredible. Right from the first preview of this, I was not down with The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, a collection of autobio strips about how embarrassing Tomine's life is.In 2020, it ended up being what seemed like the most reviewed work of the year. Not best-reviewed, but most reviewed. Tomine is a comic artist with fans in a lot of media organizations, so Rolling Stone or EW or the Guardian or the New York Times will weigh in on his work, along with lots of comic sites. And they kept saying it was very good. Everywhere kept saying it was very good! Only a few places, like Solrad, gave mixed to negative reviews of it. The thing is, the positive reviews of it highlighted what I expected would be a negative about it. The Guardian (pulled up as the top pick on an Internet search as an example) said:

In a series of autobiographical sketches from childhood to the present day, Tomine casts a cynical and unforgiving eye on his fragile ego, the dubious rewards of his successful career and the absurdity of the comic-book industry.

That doesn't sound great to me: a successful artist showing he was unhappy and frustrated in the comic industry.

|

| "This one time, I was at Dan Clowes studio, and I felt bad." |

The majority of the book is a series of vignettes where Tomine is experiencing the dream of indie success and feeling bad about it. He's one of the youngest nominees at the Eisner awards, and he feels bad. He's at a book signing in Tokyo, and he feels bad. He's the subject of a TV documentary program in Angoulême, and he feels bad.It's honest, and I'm sure he felt that way, but the jokes are only mildly amusing, not really funny, and not so insightful. For most of the book, I was just wondering why I was reading it at all.

|

| "This one time, I was a guest at the world-renowned Angoulême Comics Festival, and I felt bad." |

Around the mid-way point, he starts to add some dating themed strips. He hopes that if his girlfriend will see he's a popular cartoonist, it might impress her. This sort of detail was more endearing to me than the cringe stuff, since it was a lot more of a peek into his psychology. It's his own weakness as a person rather than the world not boosting him up enough. But this sort of thing is in a minority of the stories in the book.

The thing is, I knew from reviews and previews before I read the book that this was the main thrust of the book, and I bought it anyway. After reading, I don't think this is what the book is actually about, despite it being the majority of it. The final story is about a near-death panic he has where he reevaluates his life and everything he knows. Tomine is very frank, and direct to the reader in the form of a monologue to his wife about where his head is, that all his perceived slights are nothing compared to the love he has for his family. That final story is that Adrian Tomine magic that I love.It doesn't change that the first hundred pages of the book are a guy highlighting the negative in every aspect of a long and successful career. He got to where he is through hard work. It wasn't given to him, so I don't want to say that he isn't thankful for it. But I don't enjoy reading a book where he makes success out to be such an emotional burden.

|

| What he's really trying to say |

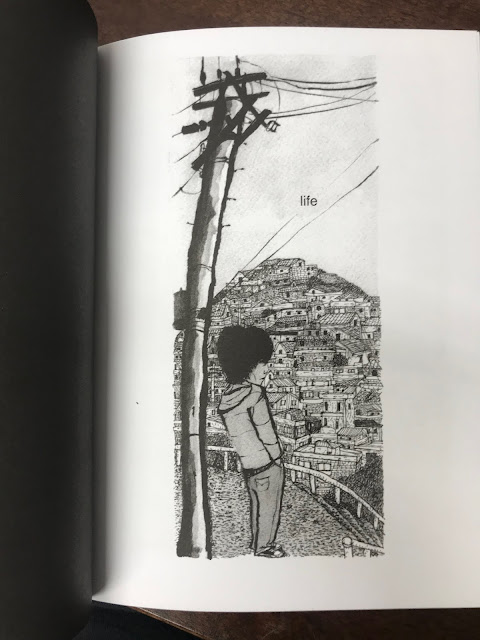

Other than that, the packaging is gorgeous. It's made up to be a Moleskine notebook, with the elastic band and everything (clout in the industry has some benefits when asking for frills in publishing at least). And the cartooning is incredible. Really incredible. He drew in this style in some of the stories in Killing and Dying. I loved it there, and I love it here too. It's very elegant, very precise, and the level of nuance in the facial expressions is simply amazing. I was regularly comparing panels to see the level of detail, for example, in jaw lines as mouths opened and closed. It's a weird thing to comment on, but it's difficult to draw and he does he perfectly. He's doing very simple images, but the structure behind them is sound.

He's at the top of his game as a cartoonist. And he's got decades ahead of him to do more great work if he chooses to.

|

| When I saw him put that text balloon tail in the third panel, I cursed the cartooning for being so elegantly simple and clever |

Books can change upon a reread. Maybe knowing that the book uses the first two thirds as a set up of the lonely cartoonist to contrast the family man learning to appreciate his life in the third act will work on a second reading. I read all his stuff twice, so maybe it won't be so frustrating next time.